PolitiHack, Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying About Russians Influencing the US Election and Learned to Love Cybersecurity

December 23, 2016 at 4:12 pm | Posted in cybersecurity, Knowledge | 2 CommentsTags: attacker, casp, ceh, cfr, CISSP, cozy bear, cybersecurity, DNC, fancy bear, fbi, GSEC, guccifer 2.0, Hackers, Russia, Security+

Hackitivism and cyberespionage are certainly nothing new, especially emanating from Russia. But the 2016 US presidential election was a swift education for Americans and the watching world regarding the widespread consequences of a successful APT (advanced persistent threat). A joint statement issued by the Department of Homeland Security and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence on Election Security stated that the “U.S. Intelligence Community (USIC) is confident that the Russian Government directed the recent compromises of e-mails from US persons and institutions, including from US political organizations” (emphasis ours).

Thanks to the detailed reporting from the New York Times, the fog of war is beginning to clear and the full extent of the cyberattack has become clear. And what is increasingly apparent is that at every stage, cybersecurity training could have significantly mitigated or (perhaps) even prevented portions of the attack altogether.

Real-time cyberthreat map from Kapersky Lab

Enter the low-rung MIS contractor hired by the DNC — Yared Tamene. He claims no cybersecurity expertise, much less any cybersecurity-related certification like GSEC, CASP, CISSP, CEH or CFR. So it’s hardly appropriate to assign him the brunt of the blame. Instead, we should use his example to learn how cybersecurity knowledge and skills could have better informed the fateful decisions that he, and many others, made along the way.

In the fall of 2015, the FBI noticed some unusual outgoing network traffic from the DNC network, suggesting that at least one computer was compromised. The early forensics linked the compromise to a known Russian cyberespionage group going by the moniker “the Dukes” (AKA “Cozy Bear” and “APT29”) , who had in just the last few years, penetrated the White House, State Department and Joint Chiefs of Staff email systems. A special agent picked up the phone, called Tamene, and told him what they knew.

Before we even get to Tamene’s response, any trained cybersecurity first responder knows why the FBI called via phone rather than emailing their dire message. Communication protocol during a security incident should be out-of-band, meaning outside of the primary communication channels (primarily network where the attacker could be listening). Ironically, Tamene was convinced that the FBI call was a hoax, and after repeated calls over the new few months, he ignored the urgency. In November, the FBI even confirmed with Tamene that known malware was routing data to servers located in Moscow.

Which actions did Tamene perform initially? He googled the term “the Dukes” and did a quick scan of DNC system logs. Unsurprisingly, he found nothing. A cursory search is good starting point, but if Tamene really wanted to know about the Dukes and their common attack vectors, he should have researched well-known cybersecurity blogs like Dark Reading and Threatpost; checked with online resources from organizations like ISC2, SANS Institute and ISACA; reviewed alert/advisory messages from Kapersky, Qualys, and Homeland Security; and, finally, reviewed known vulnerabilities from the National Vulnerability Database (NVD). As for the logs, most experienced hackers use automated log wipers and other anti-forensics techniques to avoid detection. If Tamene had listened carefully to the FBI, then he would have known the first place to begin his investigation is where the FBI detected suspicious activity: the network. Using network sniffers like Wireshark, or tcpdump/Windump to capture live traffic, or port scanning tools like netstat or even Nmap to find any unusual open ports, Tamene would have probably noticed something odd. Correlating the traffic with certain port(s) could then lead to his discovery of missing information in the logs during certain times, which in turn could have led to suspect user accounts or applications. And if he hadn’t, he could have generated a HijakThis log and crowd-sourced the investigation.

It wasn’t until professional security firms were brought in that any of these actions were performed, so the attackers were allowed to run amok throughout the DNC network.

What was their goal? In hindsight, it was clearly exfiltration. This is simply an unauthorized data transfer, and in the case of the DNC, the initial target data were the private email addresses of campaign officials and donors. This became increasingly apparent in March of 2016, when a slew of phishing emails were sent out to DNC targets, ranging from regional field directors up to the chairman of the 2016 Hillary Clinton Campaign, John Podesta. By March, Tamene was finally convinced that the FBI field agent who was calling him was indeed real (after a series of face-to-face meetings), but the damage was already done. The FBI and other private security firms believe another well-known hacking group with the moniker “Fancy Bear” (AKA “Sofacy” and “APT28”) took over operations in the second phase of the attack.

Enter the manager of the IT helpdesk on the Hillary Clinton Campaign — Charles Delavan. Despite his wealth of DevOps installation and deployment experience, he had no cybersecurity expertise beyond the basic security awareness training most employees are required to sit through. Again, no cybersecurity certifications whatsoever. Are you noticing a pattern here?

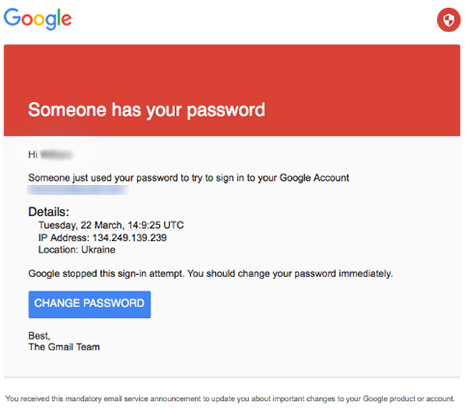

On March 19th, Podesta’s personal Gmail account received an email similar to the following :

Let me provide a little background for the uninitiated ethical hacker. This is a tricky, but not a particularly sophisticated, phishing attempt. It has the air of legitimacy, but is very easily detectable. The email did not originate from Google, nor does the Change Password link connect to Google’s servers. Instead, the link went to a spoofed site that looked like the legitimate page for changing a password, but which allowed the hackers to surreptitiously harvest the typed password. According to Motherboard’s excellent reporting, the URL behind the Change Password link was actually encoded by the popular URL shortening service, Bitly. So an easy way for Podesta or his aides to determine the legitimacy would have been to view the link’s URL and observe that it was not a Google URL. And even if the bit.ly link is decoded, its domain is not google.com, but rather google.com-securitysettingpage.tk, a top-level domain registered in the Tokelau area of New Zealand.

But the Podesta aide that read this email did not perform this most basic of security checks and instead forwarded the email to the IT Helpdesk. And Devlan responded as follows:

This is a legitimate email. John needs to change his password immediately.

Let’s unpack this response. Devlan later claimed the first sentence was a typo and the word should have been “illegitimate.” But as problematic as that first sentence is, the second is the call to action. In its ambiguity, it seems to suggest that Devlan is recommending to click the link and change the account password. Although changing the password is a good idea, Devlan should have given a legitimate URL directly through Google in which to do so and had the malicious spoofed link removed from the communications thread.

You know the rest. The aide clicked the spoofed link and the attackers, armed with his password, gained access to Podesta’s private emails. Through the moniker “Guccifer 2.0,” Fancy Bear doxed the Hillary Campaign and DNC, attempting to pin the blame on a lone Romanian hacker. The second wave of attacks went even deeper into the DNC network, supposedly going so far as to hack into Nancy Pelosi’s PC. But the motherload of doxing and media attention came with the WikiLeaks releases later in the year. And this was after the cybersecurity firms CrowdStrike secretly replaced all DNC computers and devices on the network!

There is no clearer morality tale here. It’s not a question of if, but when an organization will face a cybersecurity incident. With the ubiquitous threat and generally unprepared IT industry, has there ever been a stronger case to up your cybersecurity game with official certification test preparation from Transcender? Don’t be caught unaware by the black hats—start preparing to get certified today!

For another fascinating in-depth writeup of a related APT attack from Russia, read Crowdstrike Global Intelligence Team’s “Use of FancyBear Android Malware In Tracking of Ukranian Field Artillery Units,” published December 22.

–Codeguru

2 Comments »

RSS feed for comments on this post. TrackBack URI

The website is down! Please fix it. It redirects to this web page: https://www.transcender.com/

Comment by Juliette— January 14, 2017 #

Juliette, thanks for the notice. Which of the links were you trying to click?

Comment by The Transcender Team— January 17, 2017 #